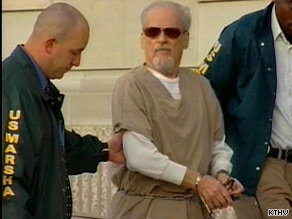

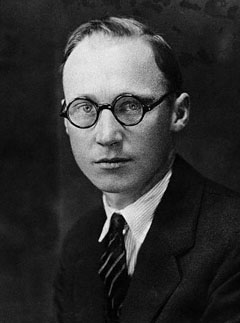

(CNN) -- When James Huberty walked into a McDonald's restaurant 25 years ago this month, he knew he was going to kill somebody. He probably didn't know his murderous rampage would change how police departments work.

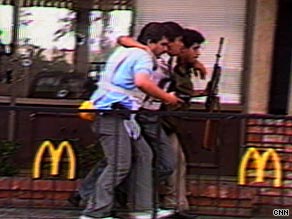

(CNN) -- When James Huberty walked into a McDonald's restaurant 25 years ago this month, he knew he was going to kill somebody. He probably didn't know his murderous rampage would change how police departments work.At 3:40 p.m. on July 18, 1984, Huberty carried a long-barreled Uzi semiautomatic rifle, a pump-action shotgun and a handgun into a McDonald's in San Ysidro, an enclave of San Diego, California.

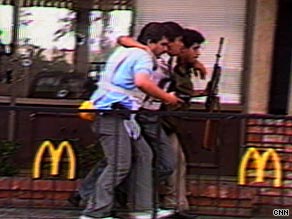

Witnesses said the unemployed welder and security guard started shooting immediately, and kept on shooting for 77 minutes until a police sniper on a nearby rooftop ended the siege with a bullet through Huberty's heart.

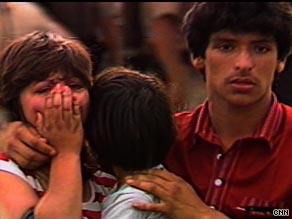

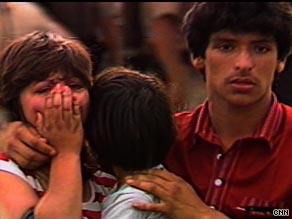

When the carnage ended, Huberty and 21 victims -- including grandmothers, an infant, children on bicycles and teenage McDonald's employees -- lay dead inside and outside the restaurant. Nineteen others were wounded.

San Diego police Capt. Miguel Rosario, a patrol officer back then, was the first cop on the scene, believing he was responding to a single accidental shooting.

Carrying a standard-issue .38-caliber revolver with six bullets, the Marine Corps veteran was in for the fight of his life against a much-better-armed opponent.

"Talk about feeling inadequate," Rosario said. "He's got an Uzi, I've got a .38, and I'm thinking it's a robbery gone bad and his buddies are going to encircle me."

Rosario would later play a key role in beefing up officers' weaponry and training to stop violent criminals.

When Rosario arrived at the McDonald's, he saw people hiding behind cars in the lot. He didn't know what was going on, but "I got that little sick feeling in the pit of my stomach," he said.

He looked up to see a man -- Huberty -- open a side door of the restaurant, the Uzi across his chest. The two men eyed each other, and then Huberty moved aggressively. The SWAT-trained officer ducked behind a parked pickup truck, "and he started opening up on me," Rosario said.

He was badly outgunned and knew it. Worse, he believed he had more than one adversary.

"I wouldn't have minded taking him on one-on-one," Rosario said in his transplanted South Bronx accent. "But if he had buddies in there and they had shoulder arms, I would have been in a world of hurt."

Huberty fired about 30 armor-piercing rounds at the officer, who could hear them striking metal posts and skipping off the asphalt.

From behind the truck, Rosario radioed in a Code 10 -- "send SWAT" -- and seconds later a Code 11 -- "send everybody."

San Diego's SWAT team then consisted of patrol officers with extra training who carried their special equipment in their squad cars, Rosario said.

Huberty retreated inside as other police units arrived. Rosario ran back to his car to retrieve his Ruger Mini-14 military-style rifle. Two patrol officers fired shotguns to cover Rosario while he took up position. But he couldn't get a clear shot.

Reporter Monica Zech had a bird's-eye view of the scene. She was giving traffic reports from a small airplane for local TV and radio stations.

"I looked down and could see that there was people ducking for cover, and there was a fire truck there with everybody behind it," she recalled. She saw two boys lying on the ground, tangled in their bicycles after being shot by Huberty, and people hiding behind the low walls of the restaurant's playground.

Circling at 3,000 feet, Zech alerted authorities to close nearby Interstate 5 and the Tijuana border crossing a few blocks away because drivers were heading straight into the line of fire.

The bright sunshine and the eatery's smoked windows made it hard for police to see inside, but eventually Chuck Foster, a police sniper on the post office roof next door, got a clear view of Huberty near the counter. Foster dropped him with a single shot through a glass door.

The battle was over, but the lessons were just beginning.

Police clearly needed more firepower and a new strategy, Rosario said.

"The time had come where you had to have a full-time, committed and dedicated, highly trained, well-equipped team ... that were committed to shooting, being in shape and being able to respond rapidly anywhere in the city," he said.

"We didn't have what we have now," Rosario said. "We have a special response team -- hostage rescue -- very elite, well-trained. It's an elite team within SWAT. We have access to helicopters now and all of that kind of stuff. We didn't have none of that back then."

After San Ysidro, the department created a dedicated unit that trains continuously and uses much more formidable weapons and tactics.

"We became pretty much special forces specialists, if you will," he said.

Police departments nationwide soon realized their own need for tactical specialists.

The San Ysidro massacre seemed to introduce a "cluster" of mass shootings in the '80s and early '90s, said James Alan Fox, a Northeastern University professor and author of six books on mass murder. These included post office rampages in Oklahoma, New Jersey and Michigan, and culminated with the Luby's restaurant slaughter in Killeen, Texas, in 1991, in which 23 people were killed.

Michael T. Rayburn, an independent police firearms trainer in Saratoga Springs, New York, said the San Ysidro incident and others -- including gangland battles of the 1920s and more recent episodes like the infamous North Hollywood bank shootout in 1997 and the Columbine school massacre in 1999 -- force police to keep developing new weapons and tactics.

"As police officers, we don't have wind tunnels or expensive laboratories. We've learned, unfortunately, out on the street, and we pay for it in blood and sometimes our lives," he said.

After the McDonald's massacre, other cities sought advice from San Diego on how to develop tactical teams. Now, such elite units are part of most larger departments across the country.

Another change after San Ysidro is how departments handle officers who have been involved in traumatic incidents. For the first time, San Diego debriefed all involved officers and provided professional counseling for those who needed it. Now, it is common practice.

"We saw the benefit and the need for that," Rosario said, though in 1984 he blew off steam in Las Vegas for two days in lieu of counseling.

Many departments still fall short, but awareness of the need for psychological services is much greater now than in the '80s, said Lynn Winstead Mabe, a police counselor and consultant in Grapevine, Texas.

"I truly think they're beginning to care about the psyche of their people," she said.